- Home

- Burmese Lacquer Trinket Box 01

Loading...

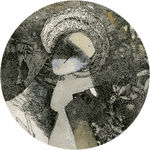

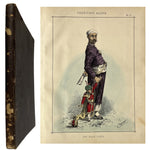

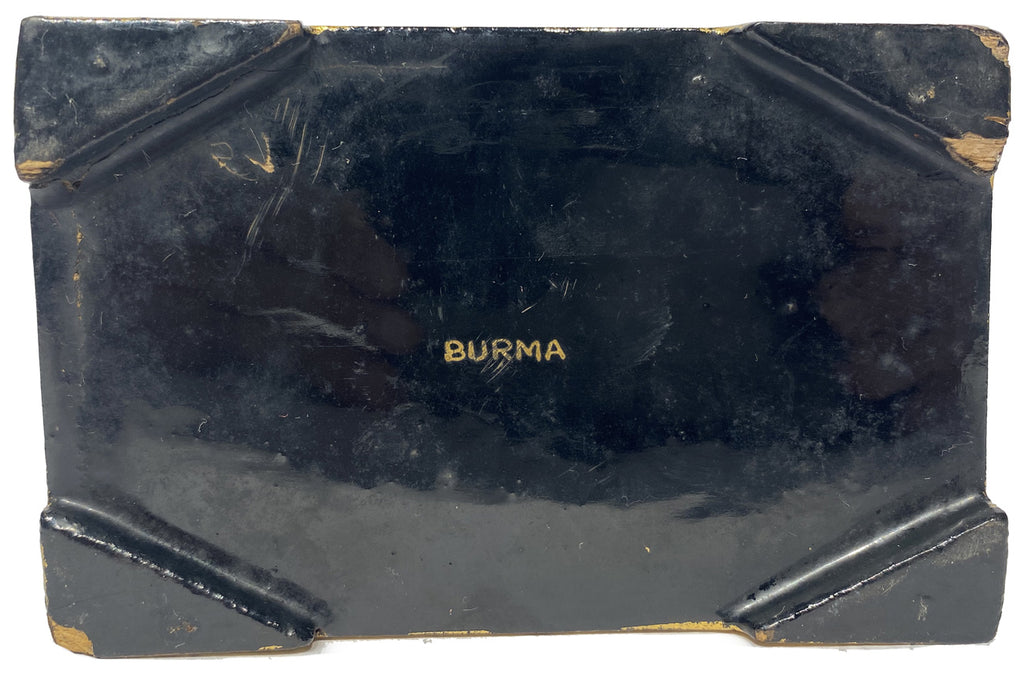

Burmese Lacquer Trinket Box 01

All orders are insured for transit.

This item cannot be shipped outside India.

All orders are insured for transit.

This item cannot be shipped outside India.

Details

| Size: | 5 x 3.25 x 2.5 inches |

| Material: | Black Lacquer and Gold Leaf |

| Origin: | Burma |

Description

-

Description

Read MoreThis is a black lacquer and gold leaf Burmese trinket box from the 1920/30s. On the lid in a black medallion is a gold chinthe, a highly stylized leogryph (lion-like creature) typical of Burmese iconography. Four coils of chu-pan foliage emanate out from this and are then held within a rectangular frame of geometric and foliate gold designs on a black background. The same coils of chu-pan foliage are repeated on the sides of the box, giving cohesion to the design. This gold leaf lacquerware is called Shwe-zaqa - it is less time consuming to produce than the more common yun ware, but is just as demanding artistically. First, on a highly polished lacquer surface, the artist carefully blocks off the areas not to be gilded with a covering of orpiment and the gum of the neem tree. By so doing, he creates a negative design for the application of gold. Then a coat of fresh lacquer is placed on the blank areas and the entire surface of the object is covered with gold leaf. When the newly lacquered areas are almost dry, the surface is washed with water. Gold on the areas covered by orpiment is washed away, revealing a brilliant gold design on a shiny lacquer background. The object is then allowed to dry in a special cellar. -

ABOUT Burmese Lacquerware

Read MoreWhile Yun-de, or lacquerware in Burmese, is considered a minor art in most countries, in Burma, it has been a dominant industry for the last three centuries. Burma acquired the techniques of production from China, where lacquer has been in use for over 3,000 years. Burmese royals often presented lacquerware as gifts to foreign envoys, and food in their banquets was served on lacquer dishes. They used lacquer boxes to store jewellery and scarves. Objects embellished with lacquer even played an important role in Buddhist religious ceremonies. But the use of lacquerware was not restricted to royalty and monkhood; lacquer objects were used daily by commoners to store food, refreshments, clothing, cosmetics or even flowers. The importance of lacquer to the Burmese is probably equivalent to the modern use of porcelain, glass and plastic combined (source: Burmese Lacquerware, book by Sylvia Fraser-Lu).

The lacquer (thit-si) is the sap tapped from the varnish tree (or thitsee) that grows wild in the forests of Myanmar (formerly Burma). It is straw-coloured but turns black on exposure to air. When brushed or coated, it forms a hard glossy smooth surface resistant to moisture or heat. Lacquer vessels, boxes and trays have a coiled or woven bamboo-strip base often mixed with horsehair. The sap is then mixed with ashes or sawdust to form a putty-like substance, which can be sculpted. The object is coated layer upon layer to make a smooth surface, and then polished and hand engraved with intricate designs. As the lacquer is very thin when applied, it requires many coats to provide an even finish. The preceding coat must be completely dry and highly polished before applying the next one. With some objects having as many as 100 such layers, the production of lacquerware was a time consuming and expensive business. It could take three to four months to finish a small vessel, and over a year for a larger piece.

Lacquer pieces came to India, specifically Tamil Nadu, through the Chettiars - a community of Indian traders, merchants and land owners, some of whom had moved to Burma. “Indians had lived in Burma for centuries, but large-scale migration took place during British-colonial rule, when the country was part of British India, during the 19th and early 20th centuries. They were used as civil servants, traders, farmers, labourers and artisans – and came to be considered the backbone of the economy.” (Source: BBC) The Chettiars originated in the Chettinad region of Tamil Nadu (about 75 villages, east of Madurai), and have been credited with the expansion of Burma’s agrarian economy. Many were also private financiers, and these banking families, although based in Burma for several generations, maintained their links with Chettinad, returning there for family events such as weddings. The family houses were kept up for this purpose and were filled with fine materials from Burma, including lacquer vessels, some of excellent quality.

-

Details

Size: 5 x 3.25 x 2.5 inches Material: Black Lacquer and Gold Leaf Origin: Burma -

Returns

We accept returns within 7 days of delivery if the item reaches you in damaged condition. -

Shipping

Shipping costs are extra, and will be calculated based on the shipping address.All orders are insured for transit.

This item cannot be shipped outside India.

This item has been added to your shopping cart.

You can continue browsing

or proceed to checkout and pay for your purchase.

This item has been added to your

shopping cart.

You can continue browsing

or proceed to checkout and pay for

your purchase.

This item has been added to your wish list.

You can continue browsing or visit your Wish List page.

Are you sure you want to delete this item from your Wish List?

Are you sure you want to delete this

item from your Wish List?

View Full Screen

View Full Screen